A great deal has been written about the 70:20:10 model recently. Some of it suggests the authors understand what the model is about. A great deal suggests otherwise.

If you and your organisation are planning to use this approach to help improve the way you build and support a high-performing workforce, it’s important that you first understand what the model is and what it isn’t.

This is where some commentators and vendors fall at the first step.

The 70:20:10 model isn’t a new interface for traditional training. It is not simply a new ‘skin’ that trainers can pull on to present their courses and workshops in new light. Of course it’s a good idea to extend structured learning into the workplace, but simply ‘tacking on’ some workplace pre-work and follow-up isn’t what 70:20:10 is all about.

70:20:10 isn’t a numbers game either. A great deal has been written about whether the ratios are ‘correct’ or not. Some respected organisations have gone down this route trying to ‘prove’ that the numbers are actually 52:27:21 or 50:26:24 or some other definitive ratio. This belies an understanding of the model.

There is no ‘perfect blend’ of 70:20:10 that organisations should be striving for in their learning strategy and activities. It’s highly unlikely you will find a ‘perfect’ 70:20:10 ratio.

Background

It’s important to understand the evidence that underpins the 70:20:10 approach is far wider than this single study.

In our book ‘70:20:10 towards 100% performance’ we cited a long list of research that has found that most learning occurs as part of the daily flow of work. Andries de Grip (Research Director and Professor of Economics at Maastricht University) reported that ‘on-the-job learning is more important for workers’ human capital development than formal training’. Many others have made similar findings – stretching back many years. In 1998 Bruce, Aring and Brand concluded that around 70 percent of learning occurs during work based. In the same year Verespej concluded that ‘62% of what employees need to know to do their jobs is acquired through informal learning in the workplace’. Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger, leaders in the area of communities of practice identified learning as occurring through trusted networks.

If you cast the net even wider, a range of experts such as the Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz provides evidence of the importance of ‘learning by doing’ from a positive economic perspective. Stiglitz’ book ‘Creating a Learning Society’ explores this in great detail from an economic point-of-view and draws on Kenneth Arrow’s work some 50 years ago. Arrow is another Nobel Laureate in Economics who wrote in his paper “The economic implications of learning by doing”[1] (Review of Economic Studies (Oxford Journals) 29 (3): 155–173). that ‘in the process of producing and investing, one learns. As we produce and invest we get better at what we do. If one builds more ships, one gets better at ship building. Productivity increases”.

The point of citing the work above is that there exists a wealth of evidence that the ‘70’ and the ’20 are important elements in the learning ecosystem. Additionally, the important lesson is that 70:20:10 should be viewed as a reference model and not a recipe. It provides a strategy to extend our focus on learning to where most of it happens – as part of the flow of work.

The ways experiential, social, and structured learning come together to build high performance will vary not only between industries and organisations, but also between job roles, specific task contexts, levels of initial expertise and probably another dozen or so factors. In other words, your own ‘70:20:10’ in any situation is unlikely to be identical to anyone else’s.

From learning to performance

70:20:10 is fundamentally an approach to help organisations move from a training mindset to a performance mindset. It is a way to place the focus onto organisational and business outputs rather than learning outputs.

This change of focus from learning to performance has significant implications for L&D organisations. This is not a minor ‘tweak’ in the way we do things. It requires learning professionals to extend their skills and activities beyond the ‘10’ – the structured learning activities with defined learning outputs – and refocus to support learning and performance improvement as part of the workflow. In many ways it requires new mindsets to develop new sets of services. For this to happen it is critical that working and learning are viewed as two aspects of the same thing.

For many L&D professionals this is sometimes difficult and virgin territory.

New Roles to Support 70:20:10

70:20:10 offers tremendous opportunities for those HR and L&D leaders who want to extend their remit and create real impact. But to do so, they need to take a fresh look at the roles, skills and tasks their teams require in order to play a meaningful part in building high performance in their organisations.

In our book ‘70:20:10 towards 100% performance’ we explain these roles and processes in detail, but they are outlined below.

It’s All About Performance

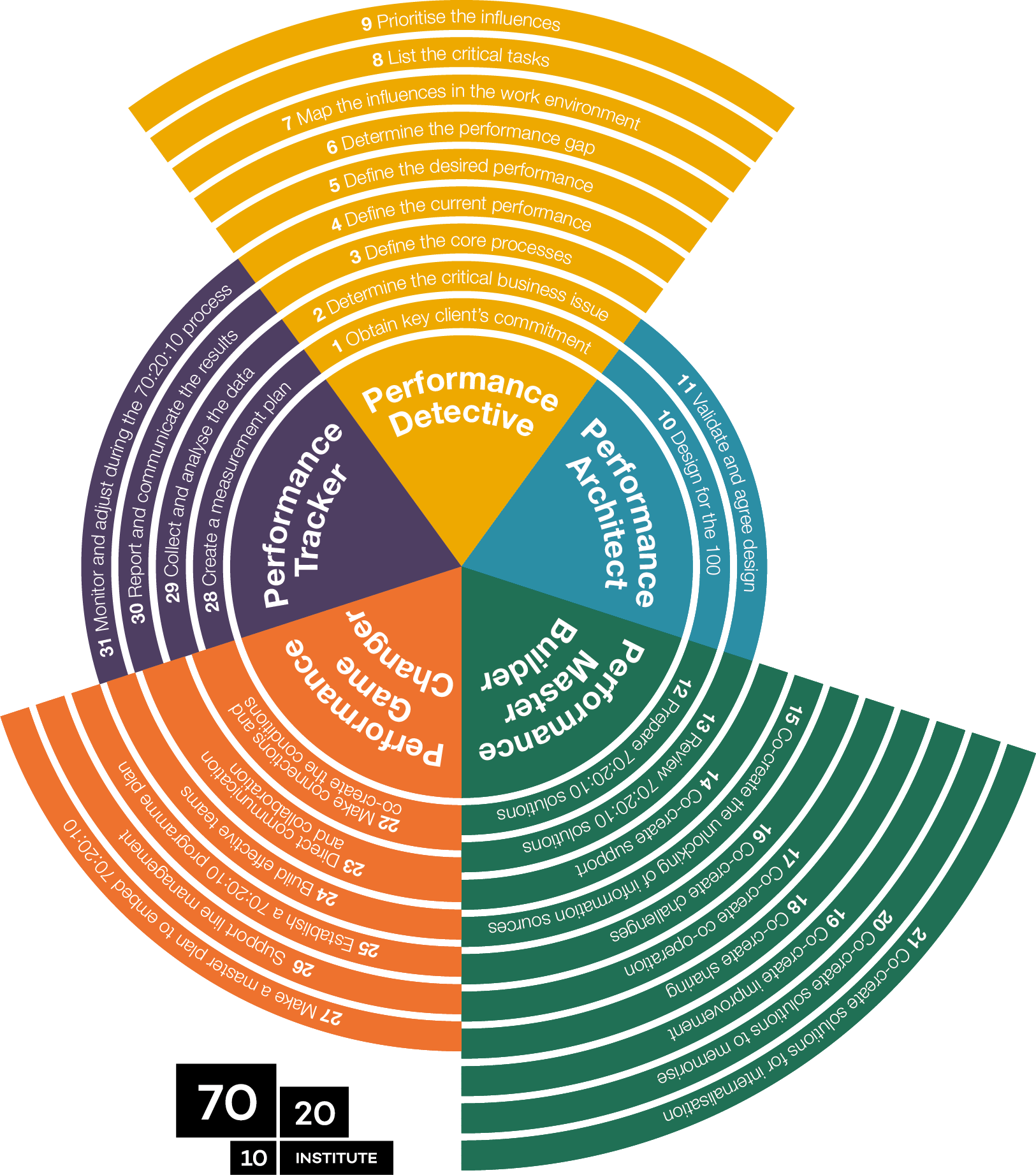

All the new roles target performance rather than learning. This is reflected in their names – the performance detective, performance architect, performance master builder, performance game changer, and performance tracker.

It’s important to understand that these roles and processes are not simply an overlay of the old ADDIE model. ADDIE was developed for military training as an instructional design model. 70:20:10 moves far beyond the need for instructional design and formal training. The new roles also do away with the rather rigid linear process embedded in the ADDIE approach. For example, the work of the Performance Tracker to define the key metrics that will be used to determine success needs to be carried out in lock-step with the work of the Performance Detective, who will determine the critical business issues, performance issues and root causes.

New Roles

It is important to understand that the new roles we have defined are interlinked and not discrete. In some cases, a single person may assume multiple roles. In other cases, a role may be filled not by a L&D professional but by someone with a different background and set of skills. Also, the tasks for each role are not all independent and don’t work in a simple linear way. Some are overlapping. Some tasks carried out by one role rely on the output from others. In other words, the roles and tasks form an ecosystem.

[1] Arrow, Kenneth J. (June 1962). “The economic implications of learning by doing”. The Review of Economic Studies (Oxford Journals) 29 (3): 155–173.

The Performance Detective:

The Performance Detective’s role is to carry out an analysis of critical organisational issues where underperformance is believed to be a contributing factor. The Performance Detective identifies the (quantified) performance gaps, the root causes of the gap, the functionalities in question and a list of critical tasks required to address the gaps (the opportunity for improvement). This goes well beyond the current role within L&D in which training needs are the focus of the analysis. The Performance Detective is focused on outputs. Training Needs are focused on Inputs.

The Performance Architect:

The Performance Architect’s role is as a business partner and designer. The Architect works closely with stakeholders to co-create solutions to the problems the Performance Detective has quantified. The key to this work is that the Architect works ‘outside-in’ to design for the ‘100’. This means starting with potential ‘70’ solutions (in the flow of work) and then with ‘20’ and finally, where necessary, with ‘10’ (formal learning) solutions. All the while the Performance Architect is focused on performance goals and team and organisational requirements.

The Performance Master Builder:

The Performance Master Builder’s role is to work on detailed development of solutions identified by the Architect that can best address the organisational issues and performance gaps. Again, this is a co-creation process together with stakeholders and high performers. Solution development is likely to be drawn from a wide range of options – including individual and social performance support, information sources, resources, tools, communities and others.

The Performance Game Changer:

The Game Changer is a role where parts may not sit within HR/L&D at all. The Game Changer has dual responsibility; to manage the implementation plan for solutions; and to manage the change processes to ensure implementation is fully embedded and sustainable. This second responsibility will include internal marketing and communications. It is likely that MarComms professionals are best positioned to lead this work.

The Performance Tracker:

The Performance Tracker role needs to work in lock-step with the Performance Detective. Without understanding how success will be measured, it is impossible for the Performance Detective to determine the opportunity for improvement. A clear set of metrics to aim at is vital at the outset. The Performance Tracker overcomes one of the challenges that many L&D teams have faced – obtaining meaningful measures of success by building a plan with the stakeholders based on clearly identified outputs right from the start.

Finally

The 70:20:10 approach, together with these roles and the myriad detailed tasks they need to undertake, has the real potential to turn the L&D function into a powerful co-creator of value across your organisation. It is an opportunity not to be missed.

If we forget about ‘the numbers’ and whether angels can dance on the heads of pins, and focus instead on the practicality of implementing the change processes that are embedded in a 70:20:10 mindset we open up a new range of opportunities for the profession.

——————————————

This article has been written by Charles Jennings, Jos Arets and Vivian Heijnen, Authors of ’70:20:10 towards 100% performance’

Book available on Amazon from December 2016.

Deluxe version is available here.