Informal learning is more important than formal learning – moving forward with 70:20:10

Learning in organisations should not be confused with attending formal courses or eLearning: people learn much more by working than they do in formal training. Informal learning takes place in the workplace where HRD (Human Resource Development) is often conspicuous by its absence, but the 70:20:10 reference model allows it to expand its range of services by facilitating both informal and formal learning, in that order. In this way 70:20:10 turns the world of learning on its head.

Research into formal and informal learning in organisations

“Learning in organisations is too important to delegate to the training department.” Jay Cross’s trenchant aphorism implies that real learning takes place informally by working, and he is not alone in his views. In the Netherlands, the educational and employment research centre ROA has been studying the roles of formal and informal learning since 2004 and has also found that most learning occurs in the flow of work. These findings, along with others that come to the same conclusions, are too important for HRD to ignore.

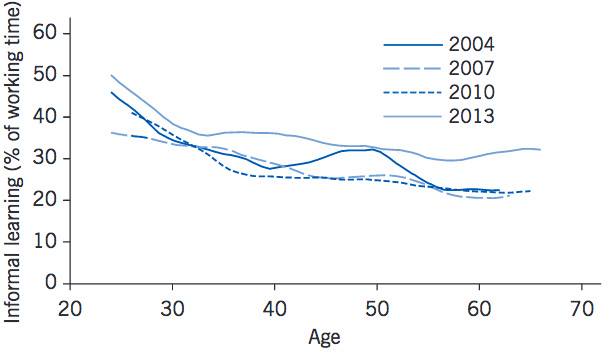

The ROA research, (Borghans et al., 2014) shows that workers spend an average of twenty-one hours a year on formal courses and other training, and 484 hours on informal learning. Fig. 1 gives an overview of informal learning by age between 2004 and 2013, showing that between 2007 and 2013, the hours of informal learning increased to 35 percent of total working time. It is also worth noting that the number of informal hours decreases significantly with age.

Informal learning is more important than formal learning

Workers spend an average of 505 hours a year learning: 494 hours informally, and 21 hours formally, or 96 to 4 percent in terms of time. This big difference alone makes it obvious that informal learning is more relevant. But in the ROA study respondents also reported they learned about the same from eight hours of formal training as from eight hours of informal learning. The learning output is the same in both cases. As a result, De Grip (2015) concludes that with equal learning output and a ratio of 96 to 4 percent, “informal learning is much more important than formal when it comes to employee development.”

Which tasks result in informal learning?

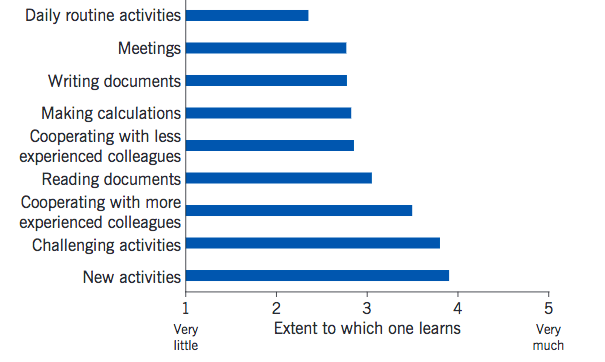

In the same study Borghans et al. asked which tasks taught employees the most. They found that a wide range of tasks provided learning input, though there were differences between well and poorly trained employees, and between women and men. Women learn more than men from meeting and working with more or less experienced colleagues. Highly trained people learn less from routine tasks than less well trained individuals, but more from challenging tasks, working with experienced colleagues, carrying out calculations, and reading documents.

Fig. 2 summarises the different tasks and how much people learn from them.

The following are some practical examples of learning by working, the 70 and 20 in the 70:20:10 reference model. Some of these fit into the categories in fig. 2; see also Arets et al., 2015.

- Learning from improvement projects in teams (20)

- After action reviews by teams (20)

- Online and offline sharing of relevant knowledge to help work more effectively (20)

- Disseminating good practice (20)

- Working out loud (20)

- Practical coaching for colleagues (20)

- Online and offline observation of an expert or top performer (70)

- Individual reflection while working (70)

- Recording online the tasks carried out during the year, and the lessons learned from each (70)

- Using performance support to ensure the quality and safety of the service (70)

- Giving presentations (70)

- Writing blogs, articles and books (70)

Today’s technology makes it easier to connect with people and learn from work. Embedded learning consists of relevant and reliable knowledge that is available online and offline, just in time, just enough, just in place, and just for you.

HRD is the dominant force in formal learning

The services provided by HRD primarily support formal learning. This is not surprising given that its people tend to be professionals with learning backgrounds, and its positioning, budgets, working processes and measurements are designed to deliver formal learning solutions. Key advantages of these formal learning include:

- Supporting employees’ personal and career development

- Making them feel more involved and satisfied

- Reinforcing informal learning

- Complying with legal and other requirements related to training

Disadvantages of formal learning

The main drawbacks of focusing on formal learning include the following:

- It creates a discontinuity in the learning process. In purely quantitative terms, based on the 96:4 percent ratio, there simply are not enough formal learning solutions available to have much impact. Formal learning constitutes too small a part of average annual working hours. This is because formal learning is not an ongoing process but a self-contained event, often with no direct connection to work and informal learning.

- People are machines for forgetting. Much of what people learn from formal learning is remembered only for a short time, unless they receive online or offline support afterwards, or can incorporate what they have learned into their everyday lives.

- The content of formal learning is not sufficiently connected with the organisation. The Association for Talent Development’s (ATD) 2014 State of the Industry report shows that over 70 percent of formal learning content is about generic and management skills. About 15 percent is directly connected to core activities, and 11 percent is compliance-related.

- Performance problems are not usually caused by knowledge deficits. Eighty percent of performance problems are the result of issues in the working environment such as poor management, inefficient processes, or lack of clarity about tasks. Willmore (2016) states it is wrong to see formal learning as “one size fits every performance problem.” You can read more about this in our classic Expensive misunderstanding: from training to business improvement (Arets and Heijnen, 2008).

- Despite all its best efforts HRD often cannot prove that it is adding measurable value for the organisation. This is always frustrating. Bersin (2016) reports that only five percent of HRD measurements are connected with organisations’ core activities.

HRD is not present during informal learning

HRD is usually not equipped to support informal learning. It provides formal solutions that are planned, organised or made available online in the form of courses, eLearning, coaching, working conferences and so on. Offering practical tasks, reflections, observations and eLearning does not constitute support for informal learning, since these are formal solutions designed to improve formal learning. This is all very well, but it does not resolve the issue of HRD’s lack of involvement with informal learning.

It is therefore reasonable to conclude that HRD faces a challenge in expanding its services to incorporate informal learning. As De Grip (2015) states, informal learning is more important than formal learning for employee development. HRD can no longer afford to turn a blind eye to the need for informal learning. It must take action to support not only the 10, but also the 70 and 20, preferably in the reinforcing context described in the 70:20:10 reference model.

70:20:10 supports both informal and formal learning

In today’s world, HRD is equipped to support the whole spectrum of informal and formal learning, using 70:20:10 and the core activities and strategic priorities of the business as its point of departure. This is a fundamentally different approach to that of formal learning, which starts with the organisation’s needs rather than those of individuals or teams.

This can be achieved using the 70, in which individual workers gain knowledge and information from the workplace that helps them to work better and learn from experience. It is also possible to learn from others online and offline, using such tools as communities, co-operation, and learning by watching.

People often learn by working together and this has an individual and a team dimension. This would be a good reason to change the name of the reference model to 90:10 – or perhaps even more precisely and based on Grip’s research, 96:4. But the numbers and ratios in the 70:20:10 model are not important. What matters is the principle that people learn most from working and in our view this is the determining factor in updating and expanding HRD services to incorporate 70:20:10.

Conclusions

- The outcomes of ROA’s research (Borghans et al., 2014) provide a scientific underpinning for the purpose of 70:20:10. What matters is not the percentages or ratios used in the reference model, but the principle that informal learning is more important to employee development than the formal variety.

- HRD is the main provider of formal learning solutions and has almost no involvement in supporting informal learning. It is the organisation’s learning department, and yet it plays no part in determining the scale and effectiveness of key informal learning activities. This is no longer acceptable.

- Many HRD departments claim to support informal learning but this is often from a formal viewpoint, for example by carrying out, observing and reflecting on tasks. But this is a 10 service and supports formal rather than informal learning.

- It is no longer sustainable for HRD to continue providing formal learning services. The world is changing fast and formal learning is primarily based on twentieth-century concepts and theories. 70:20:10 provides an opportunity to support and reinforce both informal and formal learning organisations. This is a wholly or partially new role, combining modern methods with smart learning.

- In the twenty-first century, informal learning is an inevitable and intelligent by-product of continued team improvement and renewal. By supporting informal and formal learning using 70:20:10 HRD is more closely associated with the organisation’s strategic priorities, making it the natural business partner for management in cooperation with other support departments.

Bibliography

Arets, J. & V. Heijnen. (2008). Kostbaar Misverstand. The Hague: Academic Service. Downloadable free at www.tulser.com.

Arets, J., V.Heijnen & Jennings, C. (2015). 70:20:10 towards 100% performance. Maastricht: Sutler Media.

Association for Talent Development (2014). State of the industry report. Alexandria, VA: ATD Press.

Bersin, J. (2016). The State of Learning Measurement, infographic. At: www.bersin.com/Practice. Last visited April 2016.

Borghans, L., D. Fouarge, A. de Grip & J. van Thor (2014). Werken en leren in Nederland (report). Researchcentrum voor Onderwijs en Arbeidsmarkt (ROA), Maastricht University.

Grip, A. (2015). The Importance of Informal Learning at Work. At: wol.iza.org/articles/importance-of-informal-learning-at-work). Last visited March, 2016.

Willmore, J. (2016). Performance Basics. Alexandria, VA: ATD Press.